Primary Point of Interest on the issues with the RTE and how it needs to be evolved

Times of India – May 20, 2013

Even as the deadline to implement the RTE Act expires, it’s vital that we examine factors that determine the quality of education, writes Sriram Balasubramanian.

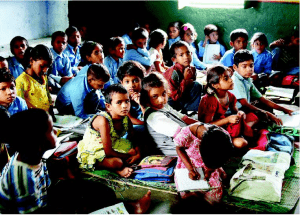

The state of primary education in India has always been a point of concern. With the RTE Act being implemented, it was expected that this would enhance both the access and scope of education to all young children across the country. But while the RTE’s potential to provide significant uplift to primary education is undeniable, some questions still remain on the quality of education provided to most. And the lines sometimes get blurred. An analysis of its impact could provide a broader understanding of why an increase in quantity does not always equal an increase in quality.

The Aser (‘ impact’ in Hindi) report produced by Pratham, a non-governmental organisation, reveals certain important facts. Firstly, it shows an increase in the number of primary schools with enrollment of 60 or fewer students in the last 3 years. This has increased from 26. 1 per cent in 2009 to 32. 1 per cent in 2012. In addition, a marginal increase has been seen in facilities across government schools with increase in drinking water facilities, toilets and the increase in mid-day meals across schools in the country. Sadly, The good news seems to stop here.

The same report also highlights some of the major issues in primary education. Top of the list are the issues pertaining to reading levels in India. In 2010, nationally, 46. 3 per cent of all children in Std V could not read a Std II level text. This proportion increased to 53. 2 per cent in 2012. This decline in reading levels is mainly in states such as Haryana, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra and even in Kerala (which happens to be the most literate state in the country). This shouldn’t surprise, because one of the major issues in public primary education has been the quality of teacher training and the pupil to teacher ratio in the system. Needless to say, poor monetary benefits provided to teachers have led to a reduction in quality of people who are entering the profession. The problems with quality of training provided to teachers has been amply highlighted in the recently conducted Central Teacher Eligibility Test (CTET) in which 99 per cent of the teachers failed to clear the exam.

Data shows that less than 1 per cent of the 7. 95 lakh who appeared managed to clear the test. While this is an indictment of the current quality of teachers in the system, it is also a reflection of the mediocre B. Ed degree coursework which enables most to teach in schools. Besides necessary curriculum reform it is imperative that teachers are provided with additional income. Without addressing these root issues it’s really not possible to have greater impact through the RTE in terms of the quality of learning imparted.

However, the level of vagueness and discretion in the RTE Act on academic quality is another vitiating factor, which needs to be addressed at another level. Take the SMC (School Management Committee) committee mechanism in government schools in rural India, for instance. This committee oversees the operations of such schools and receives funding from state and central governments for its functioning. A surveyor from Aser pointed out that these committees, by and large, do not have proper guidelines and are either inefficient or are found to be working for vested interests. Some of the parent representatives who are in the committee are not aware about why this committee has even been setup.

On another front, the Continuous and Comprehensive Evaluation (CCE) that has been initiated (for students from class 6 to 10) is a good measure but it has practical shortcomings. It is important to reduce teachers’ burden with administrative duties and focus more on CCE since it could help monitor the performance of the student on a regular basis. Overworked teachers are unable to implement these mechanisms with the energy that is required. In addition, there has been very little emphasis on skill development especially in subjects such as Maths and English. According to the Aser report, Maths and English levels have been dropping since 2007. Despite the implementation of the RTE Act such regressive trends with regard to quality abound. This is not surprising considering the increase in quantity of people in the classrooms and a lack of corresponding increase in number of teachers and infrastructure facilities in most schools, even big ones in cities. Emphasis on quality, especially in Maths and English, should involve structured mechanisms that suitably test students and also makes the teachers accountable for the performance of these students. This is not so hard a challenge to address.

Some changes in the RTE Act should also be considered, perhaps. Greater accountability for the SMC committees which monitor the performance of government schools on ground is one glaring need. A few steps will help schools match up to the lofty goals set by RTE in the long-term at the grass root levels.

But those long-term goals of the RTE Act themselves need to be met with an equal emphasis on quality and not just quantity. In this context, the focus on the RTE has to shift to pointed quality driven mechanisms that boost the ability of students in schools across the country. That cannot happen, however, unless there are thorough mechanisms put in place to increase and help maintain the quality of teachers, support robust infrastructure development across the nation, and streamline structures that that help monitor the quality of student learning across the country. Clearly, its time to address the quality issue, something we’re not often comfortable with in India.

This article can also be viewed at http://www.timescrest.com/opinion/primary-point-of-interest-10084